An international team of researchers, led by scientists at University of California San Diego School of Medicine and the University of Pittsburgh, report promising results from the largest case series yet of patients treated with bacteriophage therapy for antibiotic-resistant infections.

The findings published in the June 9, 2022 online issue of Clinical Infectious Diseases.

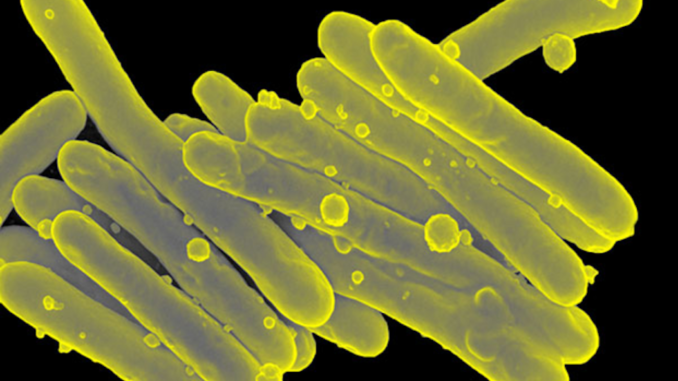

Non-tuberculosis Mycobacterium (NTM) infections are increasingly common among patients with cystic fibrosis or other chronic diseases that damage or destroy the lungs’ bronchi — the network of tubes that transport oxygen and other gases throughout the organs.

Treatment of NTM infections, particularly those caused by Mycobacterium abscessus, are difficult due to growing bacterial resistance to antibiotics, long the standard of care. The Centers for Disease Control estimates that nearly 3 million antibiotic-resistant infections of all sorts occur in the United States annually, with 35,000 resulting deaths.

Bacteriophages are viruses that have evolved to target and destroy specific bacterial species or strains. Phages are more abundant than all other life forms on Earth combined and are found wherever bacteria exist. Discovered in the early 20th century, they have long been investigated for their therapeutic potential, but increasingly so with the rise and spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

In 2016, scientists and physicians at UC San Diego School of Medicine and UC San Diego Health used an experimental intravenous phage therapy to successfully treat and cure colleague Tom Patterson, PhD, who was near death from a multidrug-resistant bacterial infection. Patterson’s was the first documented case in the U.S. to employ intravenous phages to eradicate a systemic bacterial infection. Subsequent successful cases helped lead to creation of the Center for Innovative Phage Applications and Therapeutics (IPATH) at UC San Diego, the first such center in North America.

“We think this is a revolutionary topic and study that evolved from our original Tom Patterson case report,” said co-corresponding author Constance Benson, MD, professor of medicine and global public health at UC San Diego School of Medicine. “It promises to be highly cited as we at IPATH and others work on expanding the uses of phage therapy.”

Currently, those uses are limited, in part because each phage species seeks and destroys only one bacterial species and the current armamentarium of known therapeutically useful phages is relatively small. As a result, phage therapy testing is currently constrained to experimental treatments where all other viable alternatives are failing or have failed.

The new study involved a cohort of 20 patients with complex, antibiotic-refractory mycobacterial infections. All of the patients exhibited varying underlying conditions; most had cystic fibrosis (CF), an inherited, progressive disease that causes severe damage to the lungs and other organs. Currently, there is no cure for CF. The average lifespan for persons with CF who live to adulthood is approximately 44 years.

Participating patients in the study qualified under the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s “compassionate use” provision, which allows testing of investigational drugs or products for life-threatening conditions when no comparable or satisfactory alternative therapies are available.

Benson, co-corresponding author Graham F. Hatfull, PhD, Eberly Family Professor of Biotechnology at the University of Pittsburgh, and colleagues screened 200 patients with symptomatic lung disease to identify bacterial strains likely to be susceptible to phages, and identified 55 strains.

Phages were administered to the 20 study participants intravenously, by aerosolization through a nebulizer or by using both methods twice daily over an average course of six months, though some patients had shorter or longer treatments based on clinical or microbiologic response.

Patients were monitored for adverse effects, signs of symptomatic improvement or reduced bacterial presence, emergence of phage resistance and/or neutralization of phages by the patients’ immune systems.

Results

The authors reported no adverse reactions to phage therapy in any of the patients, regardless of type of bacterial infection, types of phages used or method of treatment. Eleven of the 20 patients displayed some measure of symptom improvement or reduced bacterial presence. Five patients had inconclusive outcomes and four exhibited no response to treatment.

In eight patients, there was a noted increase in neutralizing antibodies, which may have contributed to lack of treatment response in four cases. Eleven patients were treated with a single phage, with no indications of phage resistance observed.

“Given the complexity and great variation of these patients and their individual conditions, it is not possible to draw any broad conclusions, except that phage treatment of mycobacterial infections shows promise and should be explored further,”

said Benson,

“especially for treating patients with few or no other good options.”

Hatfull said the study provided several insights into how therapeutic phages might be effectively used.

First, he said, it underscored the need to expand significantly the repertoire of useful phages, whether developing them from isolated strains or creating synthetic versions, an emerging enterprise.

Second, the lack of phage resistance was encouraging, supporting the use of a single phage treatment, though where more than one suitable phage is available, the authors suggested cycling their administration to circumvent neutralization by the patient’s immune system.

Third, optimal administration of phages, whether intravenous or aerosolization, may depend upon the nature of the infection and whether the patient’s immune system is compromised.

Fourth, because phages appear to be well tolerated with no adverse effects, higher doses and longer periods of treatment might be possible and advisable.

“All of the limitations we observed and have documented are not insurmountable,” said Hatfull. “These case studies suggest that phage treatments may be valuable tools for clinical control of NTM infections.”

Co-author Robert Schooley, MD, professor of medicine and an infectious disease expert at UC San Diego School of Medicine who is co-director of IPATH and helped lead the clinical team that treated and cured Patterson in 2016, took a longer view:

“In phages, evolution has produced an effective killer of bacteria, one that offers enormous potential in the worldwide fight against antibiotic resistance. This paper is a glimpse of what might and can be. It starts with NTM infections, but the number of antibiotic-resistant bacterial species out there is large and growing. This is another step, an important one, in a fight that will likely never end.”