Scientists from the J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI), a not-for-profit genomic research organization, UC San Diego, and a variety of international and national academic centers published a paper today in the journal Nature describing how alcoholic hepatitis may be cured through the use of bacteriophages (phages), to target specific strains of Enterococcus faecalis, the bacterium responsible for this condition. Certain E. faecalis strains secrete a substance called cytolysin, which is toxic to liver cells, killing them and thus damaging the liver.

Bacteriophages are viruses that infect bacteria. Building on research from key members of the team, it was previously understood that alcohol consumption in humans and mice promoted microbial overgrowth in the intestines. This overgrowth also shifts the composition of the bacterial species in the intestines significantly, including the newfound presence of Enterococcus spp.

In fecal samples collected from patients with alcoholic hepatitis, about 5% of the fecal bacteria were Enterococcus spp, compared with almost none in patients with alcohol use disorder or controls. Fecal samples from patients with alcoholic hepatitis had about 2,700-fold more E. faecalis than samples from controls.

Not only does alcohol consumption contribute to a shift in the bacterial population, but it also appears to increase the permeability of the gut-liver barrier, which is necessary for translocation of cytolytic E. faecalis from the intestine to the liver.

“Once we identified cytolytic E. faecalis as being responsible for the damage occurring in the liver, we began considering possible therapeutic approaches and landed on phage for its unique ability to selectively target specific bacteria,”

says JCVI scientist Derrick Fouts, Ph.D., a senior author on the study.

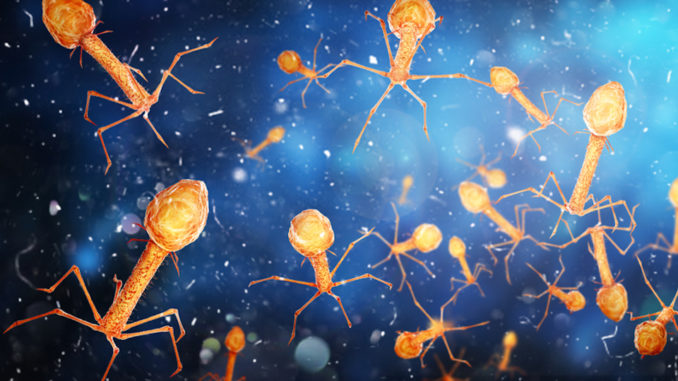

The team isolated and amplified naturally occurring phage from sewage water against the identified cytolytic E. faecalis strains. Using whole genome sequencing and electron microscopy, the lytic phages were identified as being tailed phages from the families Podoviridae, Siphoviridae, andMyoviridae.

Administration of the phages in mice significantly reduced levels of cytolysin in the liver and fecal amounts of Enterococcus. The bacteriophages targeted against cytolytic E. faecalis abolished ethanol-induced liver disease. Phages against cytolytic E. faecalis also reduced fecal amounts of Enterococcus. Importantly, phage treatment did not affect the overall composition of the fecal microbiome, intestinal absorption, or hepatic metabolism of ethanol.

“We not only linked a specific bacterial toxin to worse clinical outcomes in patients with alcoholic liver disease, we found a way to break that link by precisely editing the gut microbiota with phages,”

said senior author Bernd Schnabl, MD, professor of medicine and gastroenterology at UC San Diego School of Medicine, and director of the NIH-funded San Diego Digestive Diseases Research Center (SDDRC).

Study scientists plan on conducting additional safety tests, with the ultimate goal of advancing this potential life-saving technology to human trials.

“For widespread use of this technology, we are exploring the use of synthetic genomics and other approaches to produce phage that effectively target all cytolysin positive strains of E. faecalis,”

says JCVI scientist Derrick Fouts. The complete study, Bacteriophage targeting of gut bacterium attenuates alcoholic liver disease, can be found in the November 21 issue of Nature.

Major funding for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grants U01 AA026939 and R01 AA24726.

Research Team

In addition to the J. Craig Venter Institute and UC San Diego, researchers from the following organizations contributed to this study:

- Centro de Investigación en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas (CIBEREHD), Barcelona, Spain

- Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, NY, USA

- Hôpital Huriez, Lille, France

- Liver Unit, Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, Spain

- King’s College London, London, UK

- Pittsburgh Liver Research Center, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

- Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA

- Universidad Autonoma de Nuevo Leon, Monterrey, México

- Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

- Université Catholique de Louvain, Brussels, Belgium

- University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

- University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, USA

- University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, WI, USA

- VA-CT Healthcare System, West Haven, CT, USA

- VA San Diego Healthcare System, San Diego, CA, USA

- Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, USA

- Wellcome Sanger Institute, Hinxton, UK

- Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA

Background

The number of patients with chronic liver disease is increasing rapidly. Liver cirrhosis is now the 12th leading cause of death worldwide with more than 50% of cases associated with chronic alcohol abuse. Alcohol-associated liver disease recently became the leading cause for liver transplantation in the United States.

The most severe form of alcohol-related liver disease is alcoholic hepatitis; mortality ranges from 20% to 40% at 1–6 months, and as many as 75% of patients die within 90 days of a diagnosis of severe alcoholic hepatitis. Therapy with corticosteroids is only marginally effective. Liver transplantation is currently the only curative therapy for late stage (i.e., cirrhosis) liver disease, but is offered only at select centers, to a limited group of patients.